Bug's eye gives new view on solar

Stanford engineers are working on a way to pack tiny solar cells together, like the lenses in an insect’s eye.

Stanford engineers are working on a way to pack tiny solar cells together, like the lenses in an insect’s eye.

The bio-inspired approach could pave the way to a new generation of advanced photovoltaics using perovskites instead of silicon, the scientists say.

In a new research project, a team has used the bug-eye design to protect the fragile photovoltaic material perovskite from deteriorating when exposed to heat, moisture or mechanical stress.

The results are published in the journal Energy & Environmental Science (E&ES).

Most solar devices, like rooftop panels, use a flat, or planar, design. But that approach does not work well with perovskite solar cells.

“Perovskites are the most fragile materials ever tested in the history of our lab,” said graduate student Nicholas Rolston, a co-lead author of the study.

“This fragility is related to the brittle, salt-like crystal structure of perovskite, which has mechanical properties similar to table salt.”

To address the durability challenge, the Stanford team turned to nature.

“We were inspired by the compound eye of the fly, which consists of hundreds of tiny segmented eyes,”Reinhold Dauskardt, a professor of materials science and engineering and senior author of the study, explains.

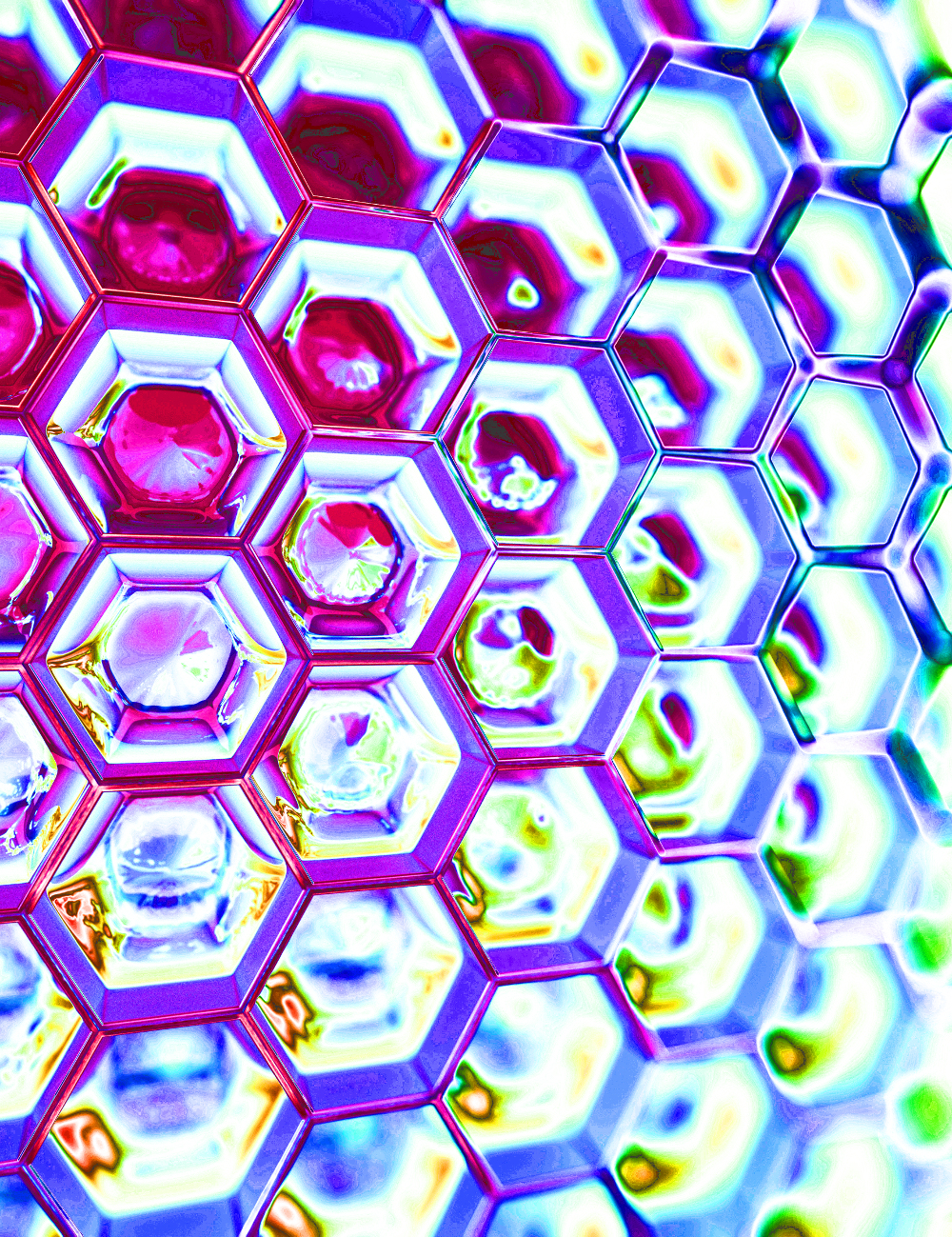

“It has a beautiful honeycomb shape with built-in redundancy: If you lose one segment, hundreds of others will operate. Each segment is very fragile, but it's shielded by a scaffold wall around it.”

Using the compound eye as a model, the researchers created a compound solar cell consisting of a vast honeycomb of perovskite microcells, each encapsulated in a hexagon-shaped scaffold just 500 microns wide.

“The scaffold is made of an inexpensive epoxy resin widely used in the microelectronics industry,” Rolston said.

“It's resilient to mechanical stresses and thus far more resistant to fracture.”

Tests conducted during the study revealed that the scaffolding had little effect on the perovskite's ability to convert light into electricity.

“We got nearly the same power-conversion efficiencies out of each little perovskite cell that we would get from a planar solar cell,” Dauskardt said.

“So we achieved a huge increase in fracture resistance with no penalty for efficiency.”

The researchers then exposed their encapsulated perovskite cells to temperatures of 85 degrees Celsius and 85 percent relative humidity for six weeks. Despite these extreme conditions, the cells continued to generate electricity at relatively high rates of efficiency.

The team has filed a provisional patent for the new technology. To improve efficiency, they are studying new ways to scatter light from the scaffold into the perovskite core of each cell.

“We are very excited about these results,” he said.

“It's a new way of thinking about designing solar cells. These scaffold cells also look really cool, so there are some interesting aesthetic possibilities for real-world applications.”

Print

Print